Case Name: Princess Cruises, Inc. v. General Electric Co.

Citation: 143 F.3d 828 (4th Cir. 1998)

Plaintiff/Appellee: Princess Cruises, Inc.

Defendant/Appellant: General Electric Co.

Issue: Whether the district court erred in applying the UCC to the contract and whether the jury erred in their award by not observing GE’s final price quotation.

Key Facts: The plaintiff submitted a purchase order (intended to be an offer) to the defendant to perform routine inspection services and repairs on one of its cruise ships. The defendant faxed back its own Fixed Price Quotation which had other terms and disclaimed any liability for consequential damages, lost profits, or lost revenue.

During the inspection, the defendant recommended that the ship be taken ashore for cleaning and balancing. During the cleaning the rotor became unbalanced, which the defendant attempted to correct. The imbalance caused further damage to the ship forcing additional repairs and the cancellation of two tend-day cruises. The plaintiff paid the defendant the full amount of the contract ($231,925).

Procedural History: A jury found GE liable for breach of contract and awarded the plaintiff $4.5 million in damages. Appealing, GE contends that the district court erred in denying its motion for judgment which required the court to vacate the jury’s award of incidental and consequential damages. GE argues that the district court erred because it applied UCC principles, rather than common-law, to a contract primarily for services.

Holding: The contract should not have been evaluated under the UCC because it was a contract for services and the jury should have only considered GE’s Final Price Quotation which restricted damages to the contract price and eliminated liability for incidental or consequential damages, lost profits, or revenue.

Reasoning: First, whether a particular transaction is governed by the UCC, rather than common or statutory law, hinges on whether the contract primarily concerns the furnishing of goods or the rendering of services. Princess’s actual purchase description requests a GE “service engineer” to perform service functions (the contract included incidental parts that were expensive).

Second, the jury should have only considered GE’s Final Price Quotation as the contract. The first purchase order submitted by Princess was rejected by a counteroffer (GE’s first price quotation) which in turn, was revoked and replaced by another offer (GE’s Final Price Quotation. Also, because Princess failed to discuss the conflicting terms of the two contracts, their inaction gave GE every reason to believe that Princess assented to the terms set forth in their final price quotation.

Restatement 19 – “The manifestation of assent may be made wholly or partly by written or spoken words or by other acts or by failure to act.” Under the Restatement, a counter-offer destroys the offer. The fact that the parties performed evidence that there was an acceptance. The phone call giving GE permission to proceed and that Princess brought their ship in to be repaired. Therefore, Princess intended to accept the last counter-offer by GE. This is called the last-shot rule. Whatever is left on the table is the contract. The only one that really matters is the last contract on the table. If the parties perform, then there is an acceptance.

Judgment: The circuit court reversed the district court’s decision and granted GE’s motion for judgment as a matter of law and remanded to modify the judgment according to common-law and the opinion of the court.

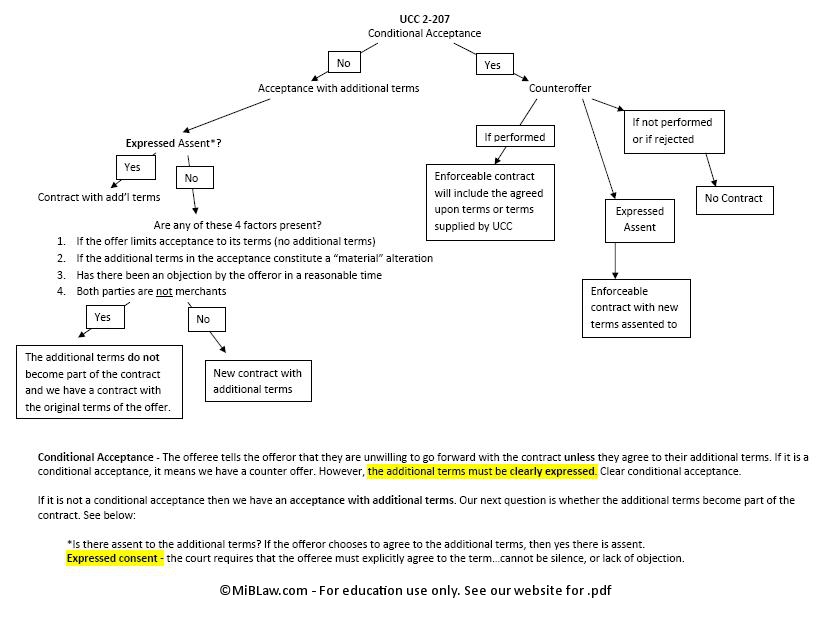

Why it was important to determine whether common law or the UCC applied: Common law only gives us two options in contract formation: Offer and Acceptance or Counteroffer. The UCC gives us a third option: acceptance with additional terms.